I will use the word "

ekklesia" to distinguish our definition from the

three common definitions of "church" suggested previously. Before we further discuss those definitions in detail, let's pause and consider a few things about our understanding of "ekklesia" and what it means for those of us hovering on the outside of the contemporary organized “church.” It is enlightening to consider that a survey of scripture on the Christian ekklesia does not specify:

1. A

numerical requirement

2. A

detailed creed/doctrinal statement

3. A

prescribed organizational structure

We'll take these one at a time, but before I get started let me clarify what I'm

not saying. I'm not saying scripture says

nothing about numbers, creeds and organization. That is simply not true. I want to be very specific here. Scripture nowhere mandates a numerical size

requirement for an ekklesia. Additionally, while

a number of creed-like statements have been identified in scripture, there is no

detailed or

unified creedal formulation found in scripture that would compare to modern creeds and doctrinal statements in either length or specificity. Finally, though there are numerous

descriptive statements about the organizational structure of the early church, there is a lack of

prescribed organizational structure. Much can be found in the Bible about how the church

did organize itself, but not about how it

must do so.

One of the prominent buzz words in “church” circles these days is

community. Particularly in the United States, there is a consistent push to draw (sometimes shame) people into church sponsored events, services, small groups or simply the church building itself in the belief that this will build community. This emphasis is often accompanied by the conviction that such "community" will preserve and increase numbers. Unfortunately, population size and growth has become the measure of the American church's success, the justification for its existence, not to mention the source of its budget. But true community has little to do with numbers and everything to do with relationship.

Community is important to people because it specifies where we

belong, where we

fit, where we will

be loved. This was an important aspect of the early Christian ekklesia as well. Jewish Christians ultimately had to leave their natural Jewish communities because they were

heterodox in their belief that Jesus was the messiah (

Acts 9:22-23). Likewise, Gentile Christians were often excluded from their communities for accepting the foolishness of a failed, crucified, monotheistic messiah (

1 Cor 1:18-25). First century Christians had only each other. The ekklesia - the church - was a community. It was often the

only community available to those who stepped out of their heritage to follow this messiah/savior in faith.

However, community within significant portions of

Evangelical church culture has come to mean something different. It has become a method of

evangelism. To some extent, this is a wonderful development. Communities of Christians should model a love and acceptance that contrasts at the deepest levels with a power-hungry, self-serving, survival-of-the-fittest kind of world.

This is not a new development. What may be considered new is the role of community in contemporary evangelism. Borrowing the common fishing analogy for evangelism, the community becomes the

lure, and the goal is to "set the hook" deeply so that coercive relational pressure may be used to draw the person to conviction, conversion and devotion. On reflection, this may seem a strikingly harsh perspective. Perhaps it is, but this is the uncomfortable, underlying motif behind numerous church communities I have encountered and it is a recurring theme in many contemporary books and articles on church leadership and evangelism. Coming from an Evangelical background myself, I think it important that we not neglect open, honest and critical analysis of our methods and motives even when they are uncomfortable to hear. I believe relationship evangelism is a beautiful thing, but we must be cautious about manipulating relationship for the machinery of "church."

Further complicating the issue is the fact that evangelism in the United States has turned

inward. There are approximately

41,000 different Christian denominations in the United States comprising

approximately 350,000 Christian congregations and only 247 million professing Christians. According to Gallup polls,

only 40% of that 247 million regularly attend church (some studies suggest only 20%), meaning that 350,000 churches are competing for roughly 99 million people (evenly distributed, that leaves 282 people per church). For this reason, the organized church in the U.S. has itself become subject to the rule of survival-of-the-fittest. Various denominations and groups devote significant amounts of time attempting to "evangelize" each other. Partially because of this, there is an inordinate amount of emphasis on "church" attendance as a sign of

obedience. Regular attendance and involvement keeps a person invested in a particular organized Christian community.

These two developments, the use of community as an evangelical tool and as a means to preserve local churches, are not inherently bad. Unfortunately, they have placed a great deal of unnecessary pressure on less socially oriented people to become something they are not in order to be obedient to God. The words of

Hebrews 10:25, "Let us not give up gathering together" (NIV) is a broad phrase and fairly applicable to small groups and partnerships outside an organized local "church."

Though it is never healthy to

completely divorce oneself from the larger body of the Church, we must remember that Jesus says, "For where two or three have gathered together in My name, I am there in their midst." (

Mat 18:20 NAU). The word "gathering" in Hebrews 10:25 (noun:

episunagógé -

gathering) and Matthew 18:20 (verb:

sunagó -

to gather) are drawn from the same root, so it is safe to acknowledge that a gathering of two or three is no less a church than an organized congregation. Even those of us who are loners need someone. It isn't good for us to be completely alone (

Gen 2:18).

Questions:

1. Do you think the description of the use of community as a "tool" within church culture is accurate? In what specific ways might it be unfair?

2. How has the emphasis on attendance by organized church communities affected you? If you are a "desert child" (someone who struggles with church culture and lives faith at the periphery of "church" culture), why is church attendance difficult for you? What kind of small group could you participate in? How could you stay connected in some way with the global/local church?

3. Given that scripture doesn't specify a number of people or a required amount of time between "gatherings" (the early church typically gathered weekly, but our passage does not mandate a specific regularity) how would you describe your ideal Christian community?

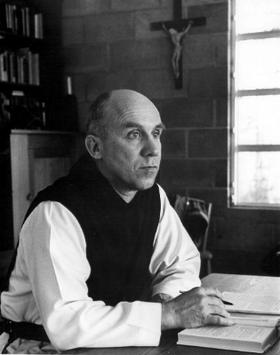

4. In upcoming posts, we will discuss the

Desert Fathers of the 4th century (the primary example for this blog). They lived solitary lives as hermits but still "gathered together semi-regularly and stayed (very loosely) connected to the Church. Does this kind of faith seem like it would be accepted by the contemporary evangelical church? Why/why not?