Though they sought their own way and their own understanding of God, these men did not hate the church. For the most part, they loved and respected the church and its leaders.2 Nonetheless, they chose to live at its periphery. Some, were "anchorites" - hermits - living almost exclusively in solitude. Others - known as "cenobites" - lived in isolated communities apart from the culture of the larger church, establishing their own "rule" and society for following Christ together.3

|

| Pachomius |

For that reason, these men are known as the Desert Fathers. We should include among them a place for "Desert Mothers" for even at the beginning, Pachomius - the great father of cenobitic monasticism - started two monasteries just for women.6 They are the spiritual forebears for many of us who are "Desert Children," spinning in a wobbly orbit of church culture. As such we may draw from the well of their wisdom, guidance and hope as we seek God in our own wildernesses.

This blog was borne out of a desire to explore that heritage, to claim our desert legacy. Once again Merton's words ring true:

It would perhaps be too much to say that the world needs another movement such as that which drew these men into the deserts of Egypt and Palestine. Ours is certainly a time for solitaries and for hermits. But merely to reproduce the simplicity, austerity and prayer of these primitive souls is not a complete or satisfactory answer. We must transcend them... Let it suffice for me to say that we need to learn from these men of the fourth century how to ignore prejudice, defy compulsion and strike out fearlessly into the unknown.7

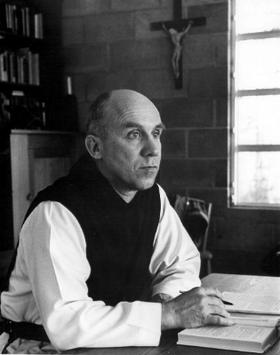

|

| Thomas Merton |

1. Merton, Thomas, The Wisdom of the Desert, p. 6.

2. Merton, Wisdom, p. 5.

3. Harmless, William, Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism, p. 18.

4. Merton, Wisdom, p. 5.

5. Merton, Wisdom, p. 10.

6. Harmless, Desert Christians, p. 115.

7. Merton, Wisdom, p. 24.

No comments:

Post a Comment